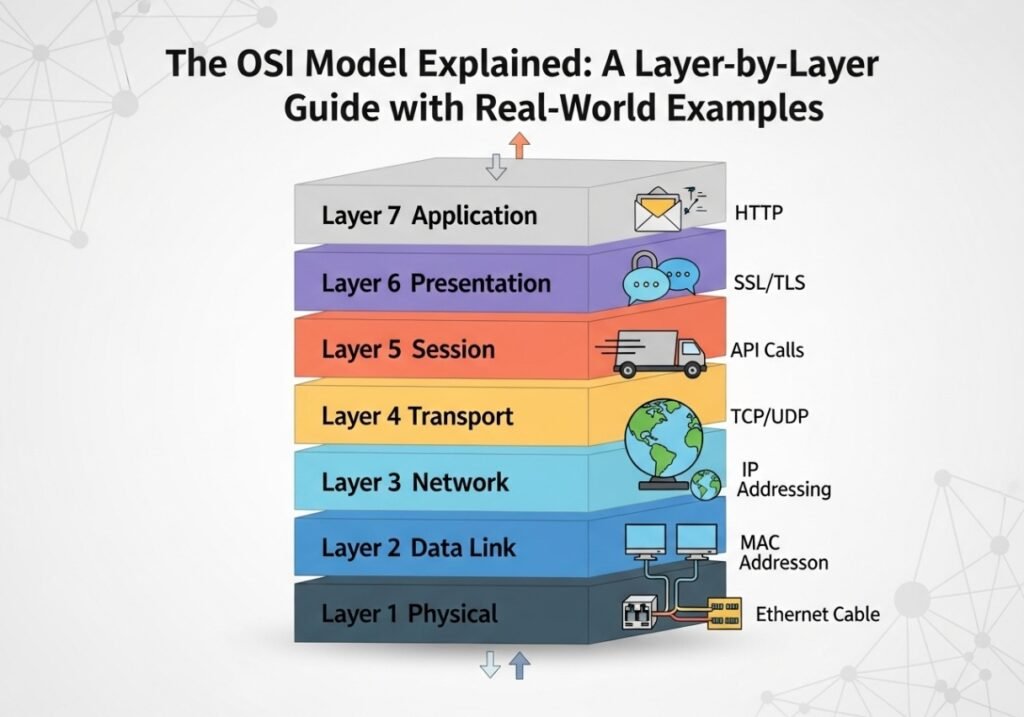

The OSI Model Explained: A Layer-by-Layer Guide with Real-World Examples

Demystifying the 7 layers of networking with a simple, practical analogy and deep technical insights you’ll actually remember.

Why the OSI Model Still Matters

If you’ve ever started learning about computer networking, you’ve undoubtedly encountered the intimidating, seven-layered beast known as the OSI Model. Developed by the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) in the 1980s, it was intended to be a universal standard for networking protocols. While the more practical TCP/IP model ultimately won the “protocol wars” and now powers the internet, the OSI model remains the undisputed champion in one critical area: **education and troubleshooting**.

The OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model provides a conceptual framework that standardizes the functions of a telecommunication or computing system in terms of abstraction layers. Think of it as the ultimate blueprint for a network conversation. It breaks down the incredibly complex process of sending data from an application on one computer to an application on another into seven manageable, distinct stages. When a network connection fails, a skilled engineer doesn’t just guess at the problem. They use the OSI model as a logical checklist, asking questions like, “Is the physical connection good (Layer 1)? Is the device getting an IP address (Layer 3)? Is a firewall blocking the necessary port (Layer 4)?”

In this guide, we’ll dissect each of the seven layers in detail. We’ll use a single, consistent real-world analogy—ordering a product from an online store—to make the concepts stick. Alongside the analogy, we will dive into the technical protocols, devices, and real-world troubleshooting scenarios that apply at each layer, transforming this abstract model into a powerful, practical tool for your networking journey.

The Core Concept: Encapsulation

Before we explore the layers, we must understand the process of encapsulation. As data travels down the OSI model from Layer 7 to Layer 1 on the sending computer, each layer adds its own header (and sometimes a trailer) containing control information. This is like putting a letter inside an envelope, then putting that envelope inside a small box, and finally putting that small box inside a larger shipping crate. Each container adds a new layer of addressing and handling instructions.

On the receiving computer, the reverse process, de-encapsulation, occurs. As the data moves up the stack from Layer 1 to Layer 7, each layer strips off its corresponding header, reading the instructions and passing the remaining data up to the next layer until only the original application data is left. This modular process is what allows different protocols and hardware from different vendors to work together seamlessly.

The name for the “chunk” of data at each layer is called a Protocol Data Unit (PDU). We will identify the PDU for each layer as we go.

Layer 7 The Application Layer: The User’s Gateway

The Application Layer is the top of the stack and the only layer that directly interacts with the end-user’s software. It provides the services and protocols that user-facing applications need to function over the network. It’s what you can actually see and click on. This layer is not the application itself (like Chrome or Outlook), but rather the set of protocols the application uses to communicate over the network.

You’re on Amazon.com. You find a new keyboard, add it to your cart, and click “Confirm Purchase.” Your interaction with the website’s interface in your web browser is the Application Layer in action. You are creating the initial request data: “I want to buy this keyboard, here is my payment info.”

Technical Breakdown

The Application Layer’s job is to ensure that the intended communication is possible. It acts as an intermediary between the software application and the lower network layers. Key protocols operating at this layer include:

- HTTP (Hypertext Transfer Protocol) & HTTPS (HTTP Secure): The foundation of the World Wide Web. Your browser uses HTTP/S to request web pages from a web server.

- SMTP (Simple Mail Transfer Protocol): Used for sending emails from an email client (like Outlook) to an email server.

- POP3/IMAP (Post Office Protocol/Internet Message Access Protocol): Used for retrieving emails from a mail server.

- FTP (File Transfer Protocol): Used for transferring files between a client and a server.

- DNS (Domain Name System): The protocol used to resolve human-readable domain names (like www.google.com) into machine-readable IP addresses.

Real-World Troubleshooting

If a user says, “I can’t get to Google.com,” a network technician might first think of Layer 7. The issue might not be the network connection itself, but a problem with the DNS protocol. If the DNS server is down, the browser (the application) has no way to translate “Google.com” into an IP address, and the connection fails before it even begins. Similarly, if you can send emails but not receive them, the issue might lie with the POP3/IMAP protocols, not the underlying network.

PDU: At this layer, the PDU is simply called Data.

Layer 6 The Presentation Layer: The Universal Translator

The Presentation Layer is often called the “syntax layer.” Its primary function is to act as a universal translator, ensuring that data sent from the Application Layer of one system is readable by the Application Layer of another system. In the modern, largely standardized internet, many of its functions are integrated into the Application Layer, but the conceptual role remains critical.

The Amazon server receives your order. To keep it secure, it uses encryption (via TLS/SSL) to scramble your credit card and address information. It also ensures your order data is in a standard format (like JSON or XML) that their backend systems can parse, and might even compress the data to save space. This translation and formatting is the Presentation Layer.

Technical Breakdown

This layer is responsible for three main tasks:

- Translation (Character Encoding): Different computers might use different encoding schemes to represent characters (e.g., ASCII, UTF-8, EBCDIC). The Presentation Layer is responsible for translating the data into a common format, ensuring that a ‘€’ symbol sent from a European computer doesn’t appear as gibberish on an American one.

- Encryption & Decryption: This is its most common modern application. When you see the padlock in your browser, it’s thanks to protocols like SSL (Secure Sockets Layer) or its successor, TLS (Transport Layer Security), which operate here to encrypt data for confidentiality.

- Compression: It can compress data to reduce the number of bits that need to be transmitted, making file transfers and video streaming faster. Common examples include MPEG, GIF, and JPEG.

Real-World Troubleshooting

A classic Layer 6 problem is a “certificate error” in your browser. This means there’s an issue with the SSL/TLS encryption process. The browser cannot verify the identity of the server it’s talking to, so it halts the connection for your security. Another example could be a web page displaying strange, incorrect characters, which might indicate a character encoding mismatch between the server and the browser.

PDU: The data is still referred to as Data.

Layer 5 The Session Layer: The Dialogue Manager

The Session Layer is the conversation coordinator. It establishes, manages, and terminates the communication sessions between applications on different devices. A session is essentially a persistent logical link that allows for an orderly exchange of data.

Before your browser sends the encrypted order data, it establishes a session with the Amazon server. It says, “Hello, I’d like to start a secure transaction.” The server agrees. This session is kept open for the duration of your transaction. If you were uploading a large photo album, this layer might place checkpoints after every 10 photos, so if the upload fails, it can resume from the last checkpoint instead of starting over.

Technical Breakdown

This layer’s functions are crucial for complex, sustained communications:

- Session Establishment, Maintenance, and Termination: It handles the entire lifecycle of the conversation.

- Dialogue Control: It determines which device can transmit and when. This can be:

- Simplex: One-way communication (like a radio broadcast).

- Half-Duplex: Two-way communication, but only one side can transmit at a time (like a walkie-talkie).

- Full-Duplex: Two-way, simultaneous communication (like a telephone call).

- Synchronization: As mentioned in the analogy, it allows for checkpoints in large data transfers, a crucial feature for reliability over unstable connections.

Protocols like NetBIOS (Network Basic Input/Output System) and RPC (Remote Procedure Call) are examples of technologies that operate at the Session Layer.

Real-World Troubleshooting

If you’ve ever been logged out of your online banking website due to inactivity, that’s the Session Layer at work! The server terminated the session for security reasons after a period of no dialogue. In a more technical scenario, an application that repeatedly fails to connect to a database server might be having a problem establishing a session at Layer 5.

PDU: The data is still referred to as Data.

Layer 4 The Transport Layer: The Quality Control Manager

The Transport Layer is where the real logistics begin. It takes the large stream of data from the upper layers and breaks it into smaller, manageable chunks. This process is called segmentation. This layer is also responsible for choosing the method of delivery, providing either a reliable, guaranteed delivery or a fast, best-effort delivery. It’s the bridge between the application-focused upper layers and the network-focused lower layers.

The Amazon warehouse system takes your complete order (keyboard, mouse, monitor) and segments it. It chooses a shipping service: for this important order, it uses TCP (like FedEx with tracking). It packages the items into three separate boxes, numbers them “1 of 3,” “2 of 3,” “3 of 3,” and includes instructions that you must sign for each one upon arrival to confirm receipt. If a box is damaged or lost, it will be resent.

Technical Breakdown

The two workhorse protocols of this layer define its function:

- TCP (Transmission Control Protocol): This is the reliable, **connection-oriented** protocol. Before sending data, TCP establishes a formal connection using a process called the **three-way handshake (SYN, SYN-ACK, ACK)**. It uses sequence numbers to track each segment and acknowledgements (ACKs) from the receiver to guarantee that every segment arrives in the correct order and without errors. It also provides **flow control** to avoid overwhelming the receiver. This makes it perfect for web browsing, email, and file transfers where data integrity is paramount.

- UDP (User Datagram Protocol): This is the fast, lightweight, **connectionless** protocol. It’s “fire-and-forget.” It wraps data in a simple header and sends it out without establishing a connection or waiting for acknowledgements. It’s much faster than TCP but offers no guarantee of delivery or order. This makes it ideal for real-time applications like video streaming, online gaming, and VoIP, where speed is more important than perfect reliability.

This layer also adds **source and destination port numbers** to each segment. A port is a logical endpoint that allows a computer to handle multiple network conversations at once (e.g., port 443 for HTTPS traffic, port 25 for SMTP).

Real-World Troubleshooting

A network administrator uses Layer 4 knowledge constantly. If a web server isn’t responding, they’ll use a tool like `telnet` or `nmap` to check if port 80 or 443 is open and listening. A choppy, pixelated video call is a classic symptom of UDP packet loss over a poor connection. A firewall rule blocking a specific TCP port is one of the most common reasons an application fails to connect to its server.

PDU: Segment (TCP) or Datagram (UDP).

Layer 3 The Network Layer: The Global Postal Service

The Network Layer is responsible for moving data across different networks, a process known as **routing**. It takes the segments from the Transport Layer and adds a logical address header, creating a **packet**. This header contains the most important address on the internet: the **IP address**.

The Amazon shipping department takes each numbered box (segment) and slaps a full shipping label on it. This label contains your complete street address (destination IP) and the warehouse’s return address (source IP). This globally unique address allows any postal service in the world (the internet’s routers) to work together to figure out the best route of planes and trucks to get the packet from the warehouse to your city’s local post office.

Technical Breakdown

This layer is the domain of routers and logical addressing:

- Logical Addressing: The Network Layer uses **Internet Protocol (IP)** addresses (both IPv4 and IPv6) to identify devices on the internet. Unlike a MAC address which is fixed, an IP address can change depending on the network the device is on.

- Routing: This is the core function. **Routers** operate at Layer 3. They examine the destination IP address of an incoming packet and consult their internal **routing table** to determine the best path to forward the packet towards its final destination. Routing tables are built using dynamic routing protocols like **OSPF (Open Shortest Path First)** and **EIGRP**.

- Path Determination: It figures out the best way to send the packet through the complex web of interconnected networks that make up the internet.

Real-World Troubleshooting

Layer 3 is the home of the most famous networking tools: `ping` and `traceroute`. When you `ping` google.com, you are sending a Layer 3 packet to see if you can get a response. When you use `traceroute`, you are sending a series of packets to map out every single router (or “hop”) the data takes on its journey from your computer to the destination server. If a `traceroute` fails at a certain hop, you know exactly where the communication breakdown is occurring in the global network.

PDU: Packet.

Layer 2 The Data Link Layer: The Local Delivery Driver

If the Network Layer handles global, city-to-city delivery, the Data Link Layer handles local, door-to-door delivery on the same physical network. It takes packets from Layer 3 and wraps them in a header and trailer to create a **frame**. The crucial piece of information added here is the **MAC (Media Access Control) address**—the unique, permanent hardware address burned into every network interface card (NIC).

Your package has arrived at the local post office (your router). The global IP address got it this far. Now, the Data Link Layer’s job is to put that package on the specific mail truck that serves your street. The driver uses your unique house number (your device’s MAC address) to deliver it from the post office to your exact front door. The driver doesn’t need to know where the package came from globally, only how to navigate the local streets.

Technical Breakdown

The Data Link Layer is divided into two sublayers:

- LLC (Logical Link Control): Acts as an interface to the Network Layer above, identifying which protocol is being used (e.g., IP).

- MAC (Media Access Control): Responsible for physical addressing and controlling access to the network media. This is where the MAC address lives. **Switches** are the primary devices that operate at Layer 2. They build a MAC address table to learn which device is on which physical port, allowing them to intelligently forward frames only to the intended recipient.

This layer also performs error detection using a **Frame Check Sequence (FCS)** in the trailer. If a frame is corrupted by interference, the receiving device will detect the mismatch and discard the frame.

Real-World Troubleshooting

A common issue is a faulty ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) cache. ARP is the Layer 2 protocol used to map a known Layer 3 IP address to an unknown Layer 2 MAC address. If this mapping is wrong, packets can’t be framed correctly for local delivery, and communication fails. A technician might clear the ARP cache (`arp -d`) to resolve this. On a larger network, an administrator might check a switch’s MAC address table to see if a device is physically connected and visible to the network.

PDU: Frame.

Layer 1 The Physical Layer: The Wires and Waves

We’ve reached the bottom. The Physical Layer is all about the hardware. It is responsible for the actual transmission and reception of the raw, unstructured data—the stream of ones and zeros (bits). This layer defines the physical characteristics of the network, from the type of cable used to the voltages of the electrical signals.

This is the physical road itself. It’s the asphalt, the traffic signals, and the physical tires of the mail truck. The Physical Layer doesn’t care about the package, the address, or the driver; its only job is to provide the physical medium for the truck (the signal) to travel from one point to another.

Technical Breakdown

This layer encompasses all the tangible parts of the network:

- Media: Ethernet cables (Twisted-Pair Copper), Fiber Optic cables, Coaxial cables, and Radio Frequencies (Wi-Fi, Bluetooth).

- Hardware: Network Interface Cards (NICs), hubs, repeaters, transceivers, and cable connectors (like RJ45).

- Signaling: Defines how bits are represented on the medium—as electrical voltages, pulses of light, or radio waves.

Devices like hubs and repeaters are considered Layer 1 devices because they only understand electrical signals; they don’t read addresses and simply regenerate and repeat any signal they receive.

Real-World Troubleshooting

This is the first place any technician starts. “Is the cable plugged in securely?” “Is the link light on the network card lit up?” “Is the cable damaged, cut, or too long?” “Is there significant wireless interference from a microwave oven?” These are all Layer 1 questions. A faulty cable or a bad network port are extremely common points of failure, and they all fall under the Physical Layer.

PDU: Bits.

OSI vs. TCP/IP Model

While the OSI model is a 7-layer conceptual framework, the modern internet runs on the 4-layer (or sometimes 5-layer) **TCP/IP model**. It’s more practical and maps directly to the protocols used online. Here’s how they relate:

| OSI Model Layer | TCP/IP Model Layer | Key Protocols |

|---|---|---|

| 7. Application 6. Presentation 5. Session | Application | HTTP, SMTP, DNS, FTP |

| 4. Transport | Transport | TCP, UDP |

| 3. Network | Internet | IP, ICMP, ARP |

| 2. Data Link 1. Physical | Network Access | Ethernet, Wi-Fi, MAC addresses |

The OSI model’s value lies in its granularity. By breaking down the Application and Network Access layers into more specific functions, it provides a more detailed blueprint for understanding and troubleshooting network processes.

Summary & The Troubleshooting Mindset

The OSI model is more than an academic exercise; it’s a way of thinking. It teaches a structured, top-to-bottom or bottom-to-top approach to problem-solving that is invaluable. By understanding the specific job of each layer, you can logically deduce where a failure is most likely occurring and choose the right tool to investigate it.

From the application you click on, through the complex web of routers and switches, all the way down to the electrical pulses in a wire, you now have a map of the complete journey. You’ve taken a massive step toward not just using the network, but truly understanding it.

I love your writing style genuinely loving this internet site.

Only a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding design.

Thanks for the appreciation.

Hello, you used to write fantastic, but the last several posts have been kinda boringK I miss your great writings. Past several posts are just a little bit out of track! come on!

Once I initially commented I clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now each time a remark is added I get four emails with the same comment. Is there any means you possibly can remove me from that service? Thanks!

I would like to show my appreciation to the writer just for bailing me out of such a circumstance. Right after looking out throughout the internet and coming across methods which are not powerful, I was thinking my life was done. Living minus the strategies to the issues you have resolved by way of this short post is a crucial case, and the ones that would have badly damaged my entire career if I hadn’t encountered your site. Your good talents and kindness in handling the whole lot was invaluable. I am not sure what I would have done if I hadn’t come across such a stuff like this. I am able to now look forward to my future. Thank you so much for your skilled and amazing guide. I won’t think twice to suggest your web blog to anybody who needs guidelines on this issue.

Thanks for your appreciation about the site, I hope you enjoyed the articles and please share your invaluable thoughts like this to encourage us for putting these articles on this site.